I was going to wait and post this later after I head back from a few more Exidy employees I've contacted, but I decide to go ahead and start it now. I'll update it if I get more info (or include the info in the book).

Today's post actually covers Ramtek, not Exidy. You'll see why if you read it

Ramtek

Like Atari, Ramtek was located in Sunnyvale but unlike Atari, it didn’t start out as a video game company. Founded in 1971 by brothers Chuck and Mel McEwan and three other aerospace engineers (with funding from Exxon Enterprises), Ramtek manufactured graphic displays and imaging hardware, primarily for the medical industry. In its early years the company grew via "bootstrapping" - borrowing money from anyone it could and plowing all profits back into manufacturing.

Today's post actually covers Ramtek, not Exidy. You'll see why if you read it

PART 1

While PSE and Meadows were both located in Sunnyvale, neither company would make any video games after 1978. Another Sunnyvale company, Exidy, was a different story entirely. At its height, Exidy was third only to Atari and Bally/Midway among U.S. video game producers and created a handful of hits that are among the minor classics of the era. The roots of the company, however, extend to another short-lived Sunnyvale competitor – Ramtek.Ramtek

Like Atari, Ramtek was located in Sunnyvale but unlike Atari, it didn’t start out as a video game company. Founded in 1971 by brothers Chuck and Mel McEwan and three other aerospace engineers (with funding from Exxon Enterprises), Ramtek manufactured graphic displays and imaging hardware, primarily for the medical industry. In its early years the company grew via "bootstrapping" - borrowing money from anyone it could and plowing all profits back into manufacturing.

With the introduction of Pong, Ramtek jumped on the lucrative videogame bandwagon. Ramtek, in fact, may have gotten a look at the game before any of Atari's other competitors. Al Alcorn reports that not long after he'd placed the prototype Pong for test at Andy Capp's Tavern he noticed a group of "customers" who came in every morning at 9 to play the game. This struck him as odd since most bars were empty at that early hour. When he asked owner Bill Gattis about it, Gattis told him they were engineers from Ramtek[1]. Nolan Bushnell claims that one of the owners of the bar was actually Ramtek's financial Vice President[2].

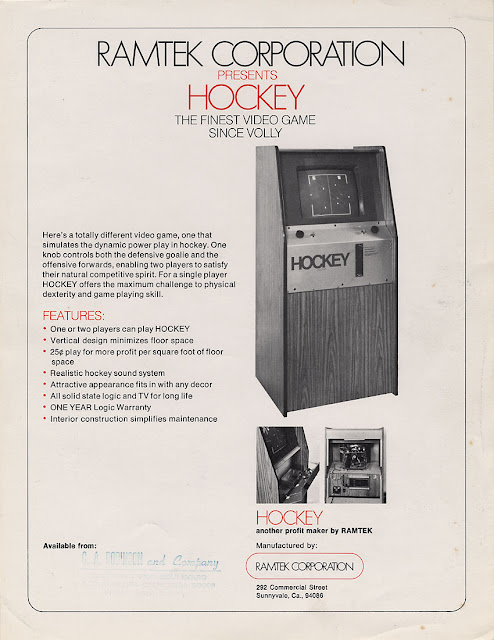

It should be no surprise, then, that Ramtek started with Pong clones like Volly, Hockey, and Soccer (all 1973). The games had their share of issues. Volly, for instance, came in a lovely round-topped cocktail cabinet but there was a small problem – the game was too large to fit through the doors of most locations. A bit more sophisticated was 1974’s Baseball (with cabinets built by Tempest Products, who also built cabinets for Atari). Wipe Out (January 1974) was a 2 or 4 player game similar to Atari’s Quadrapong but with a twist in the form of a special “frustration bumper” that would cause the ball to bounce in a random direction. By 1974, the company had $6 million in sales, had manufactured more than 10,000 video games and was looking to expand its facilities. Howell Ivy was one of Ramtek’s chief game designers. Before coming to Ramtek, Ivy spend 7 1/2 years in the Air Force, working on missile instrumentation at their Satellite Test Center. Ivy’s first game for Ramtek was Clean Sweep (June 1974) a pinball-like game he had started designing in 1973 in which the player controlled a paddle to direct a ball towards a field of dots. The object was to eliminate all of the dots while not letting the ball get past you. Some see the game as a predecessor of sorts to Atari’s 1976 hit Breakout but the gameplay was actually quite different. The “bricks” filled almost the entire screen and the ball eliminated every dot in its path rather than bouncing off them. Ivy also worked on a number of other games at Ramtek, including Trivia (1975), a quiz game with questions loaded in via interchangeable 8-track cartridges, and Barricade (1976), a version of Gremlin’s much-copied Blockade. Gremlin, in fact, brought suit against Ramtek in January of 1977 over the similarities of the names of the two games and Ramtek agreed to use the name Brickyard if they continued to make the game (they didn’t).

At a March 1976 distributors meeting (with special guest comedian Pat Paulsen), Ramtek announced that it had sold 20,000 games in its first three years and was going to split its game and computer displays divisions into separate companies. In November of 1976 disaster struck - or so it seemed at first. Back in 1974 Ramtek was set to launch a new line of color monitors but needed to raise $1.4 million to do so. By November of 1976 they had finally struck a deal giving them the funds they needed. Then, the night before Chuck McEwan was scheduled to fly back east to close the deal, Ramtek's $7 million manufacturing plant burned down. They had allowed their insurance policy to lapse just a month before. In truth, however, the fire proved to be a turning point for the company. An emergency meeting was called with the company's bankers, who provided enough funding to keep Ramtek afloat and the episode caused the company's employees to pull together into a community[3].

Ramtek had already started producing more sophisticated video games such as Sea Battle (April 1976), which featured multi-player ship-to-ship combat where players could “blow away islands” and “hide in coves” while trying to destroy the opposing vessels and avoid deadly mines. Star Cruiser (September 1977) was a kind of Spacewars without the central sun that featured controls usually seen in driving games – a U-shaped steering wheel and a gas pedal. Ramtek’s most popular game was probably M-79 Ambush (1977), which featured a gun attachment modeled after the army’s M-79 grenade launcher. In Replay’s year-end survey of the best games of 1977 M-79 Ambush was among the 15 video games listed. Two of Ramtek’s final arcade game releases were Dark Invader (a non-video space-themed game in which the player looked through a porthole to view the playfield, which made use of a laser, a spinning mirror, and fluorescent targets to create a stroboscopic effect), released in August of 1978, and GT Roadster (a non-video projection film driving game released in December). After 1978, Ramtek stopped producing video games entirely, though they did continue to manufacture the non-video game Boom Ball. The game was similar to Skee Ball but instead of rolling the balls, the player shot them out of a cannon. Boom Ball proved extremely popular and Ramtek continued producing it until mid-1980 when they sold it, along with their entire games division to Mel McEwan (cofounder of the company and manager of the division). The problem was that the division was losing money, and apparently had been for some time. In its 1980 annual report, Ramtek reported that they'd lost $971,000 in 1979 from "discontinued operations" and had posted smaller losses in 1977 and 1978. Most, if not all of this, was probably from their games division. Overall, the company had turned a profit but in 1979 profits had declined to just $283,000 from a high of $1.3 million the year before. After buying the games division, Mel McEwan created a company called Meltec and continued to produce Boom Ball.

![]()

After selling the games division, Ramtek returned full time to the fields it knew best – medical imaging and CAD/CAM. 1980 saw sales of $25 million with plans to begin manufacturing PC monitors, but as far as video games went, the company was finished.

In terms of video game history, however, Ramtek’s main contribution came not from its games, but from three of its employees. Harold R. “Pete” Kaufmann was an early partner at Ramtek who left in 1973 with plans of forming his own company with the sole purpose of creating video games. Designer John Metzler followed and in 1975, designer Howell Ivy decided to move on as well and he joined Kaufmann at his newly formed venture.[1] Al Alcorn interview, Retro Gamer #88

[2]Interview, Play Meter, June-July 1975.

[3] The dates given for the fire come from Malone The Big Score p.300. The December 24, 1975 issue of Computerworld reports that a fire on the morning of 20th "had rendered 10,000 square feet of manufacturing space unusable." This may have been a separate fire or Malone may have got his dates wrong.