Here's a summary of a few other major 1980s video game tournaments.

On of the earliest big-money national tournaments was the Putt Putt $10,000 Pac-Man Tournament in the summer of 1981. Local and regional qualifiers were held at Putt Putt Golf & Games locations nationwide to pick three finalists, who competed in Fayetteville, NC (Putt Putt headquarters) on August 30th to crown a champion. 17-year-old Steve Hair of Columbia scored 372,600 points, edging out Chris Johnson and Mark Spina for the $5,500 first-place prize. The tournament did well enough that Putt Putt announced that they would be offering over $50,000 in prize money in 1982 in a series of $10,000 tournaments. The tournaments ended up being only $5,000 tourneys rather than $10,000. The Centipede tournament took place in January of 1982 with the finals on January 31st. Finalists played a 20-minute game at their local Putt Putt locations with their scores being called in to Putt Putt HQ. Larry Henderson of El Paso won the $2,000 first prize with a score of 299,816. The Tempest finals took place on March 28th with Curtis Kidwell of Arlington, TX taking home the two grand, scoring 409,381 points in 20 minutes. A third $5,000 tournament was scheduled for later in the spring but it isn't known if it ever took place.

1981 California State Championships

Not a tourney, but here's Craig Steele setting a record on Star Castle in 1981

Putt Putt National Tournaments

| Putt Putt $10,000 Pac-Man Tournament |

A few months later husband-and-wife operators David and Marianne Davidson, hoping to repair the black eye the industry had received at the Atari $50,000 World Championships in October (see below), spent $60,000 of their own money to organize another California State Championship held at 200 Stop N Go locations with the finals at the Ramada Inn in Culver City on December 19 on Defender. Fifteen-year-old Jeff Davis won the contest and a new Defender arcade game.

1984 March of Dimes International Konami/Centuri Track & Field Challenge

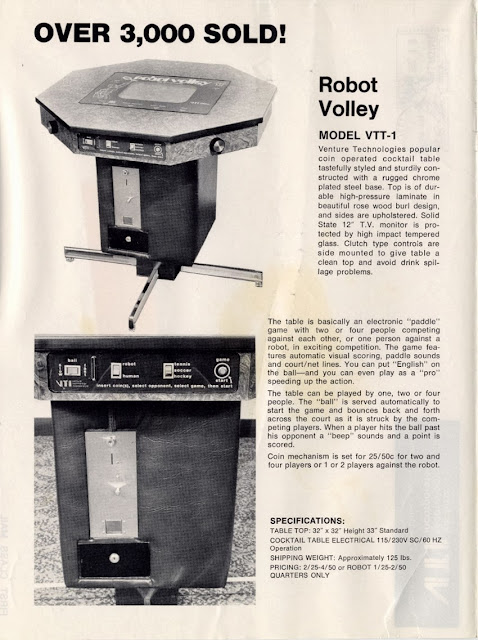

Held in spring of 1984, this tournament not only had the longest name of any tournament but it is considered history's largest arcade video game tournament with over a million contestants (800,000 in the U.S. and 200,000 in Japan). The U.S. Qualifying rounds took place from April 30 to May 25 at Aladdin's Castle and National Convenience Storelocations (like Stop N Go and Hot Stop Markets). One qualifier from each of the 14 regions went to the four-round finals in Houston on May 26. Winner Gary West along with runners-up Phil Britt and Mike Mallory, travelled to Tokyo to face the top three Japanese finishers - Shinichi Takahashi, Akihiro Oozono, and 14-year-old champion Hideki Houchi . The three were put up at the Grand Palace Hotel (the event venue), given a two-day tour of the resort town of Nikko, and feted at a ceremonial dinner complete with Japanese performers. The presidents of Konami and Centuri were on hand for the main event, which took place on June 9. In the first round, players competed individually on each of the game's six events with Phil Britt winning four of them. The U.S. won the second round, in which each team was given twenty minutes to rack up as many points as possible, 220,000 - 140,000 (interestingly, the Japanese team played on cocktail machines while the US chose uprights). In the final round, each player played three games with only their top score counting. Using their "finger roll" technique, Britt and West finished first and second. All contestants won medals and loving cups and the US team got Seiko watches.

And here are some assorted pictures from other tourneys

First up, here's the winner of the 1974 Japan tournament I posted about earlier:

This wasn't a video game tournament, but here's Ken Lunceford, winner of the 1978 Bally Supershooter Tournament (billed as the first national pinball tournament).

Here's a picture from the Atari $50,000 World Championship fiasco:

Did you know that Billy Mitchell had a Siamese Twin? Here's proof from before the separation in 1984.

And here's another shot of the US National Video Game Team, circa March, 1984:

Houston Malibu Gran Prix Armor Attack Tourney - August, 1981

Tron World Championship - May, 1982

Captain Video Scramble Tournament - August, 1980

Stop N Go Krull Tourament, December 1983.

Easter Seals 10-Yard Fight Championship, August, 1984

First Annual Vs. Tennis Open, August 1984

Olympic Arcade Tricathalon - 1980

Not a tourney, but here's Craig Steele setting a record on Star Castle in 1981

Finally, here's an article from Vending Times about an all-but-forgotten attempt at an early attempt at forming a video game player's league

.jpg)