I haven't done one of these in a while. This time, I'm only going to do a single year because I consider 1978 to be the last year of the "Bronze Age" (1979 was kind of a transition year).

1978

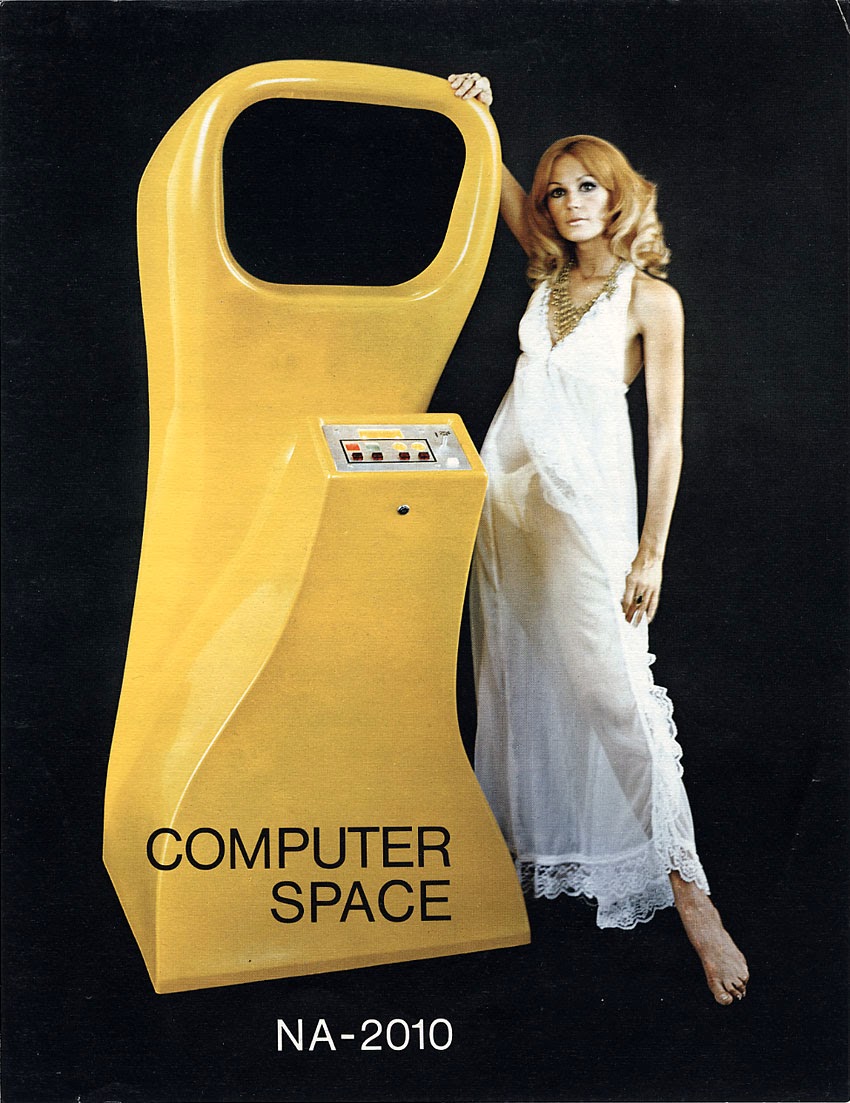

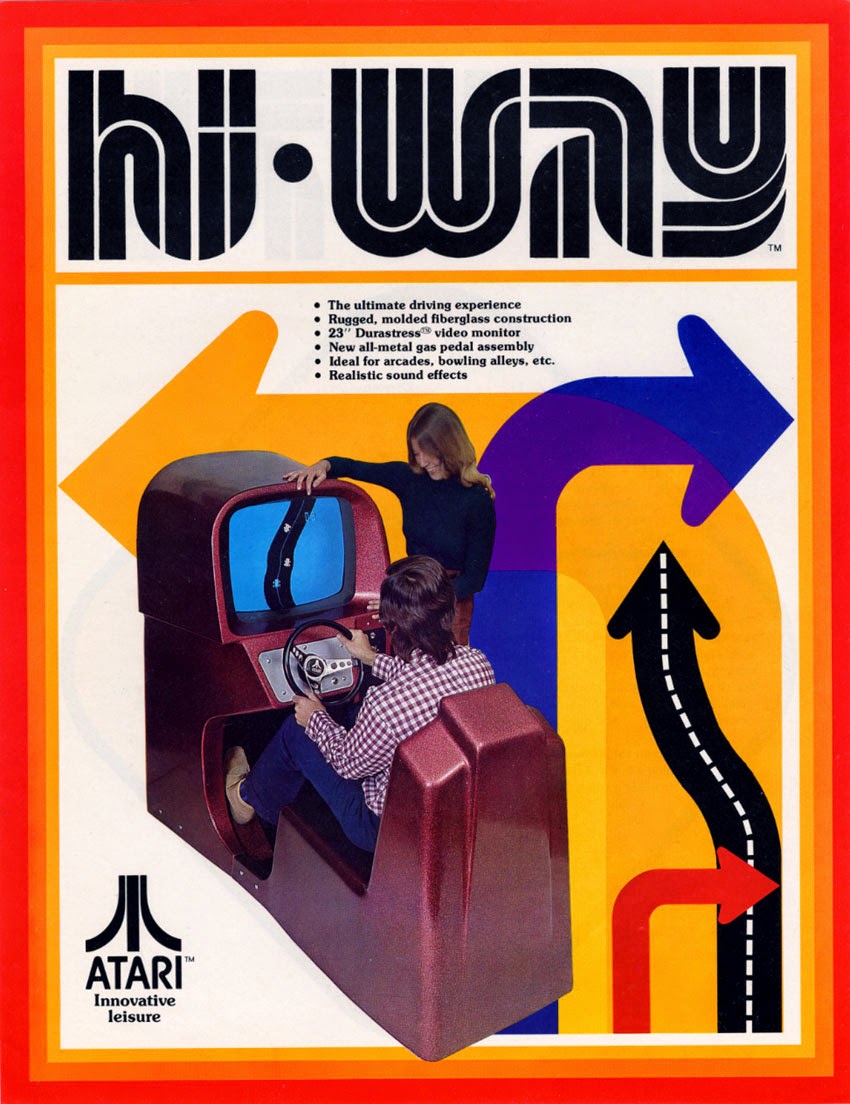

RePlay’s annual review said of 1978 "Video games…disappointed this past year. Unfortunately, they were off in both sales and route collections in all parts of the country. It was probably the most disappointing year in the history of this college-bred phenomenon of the coin industry." They also noted that the year was "less than a banner year" for the coin-op industry in general (outside of pinball and foosball). The main issues were over saturation and poor quality control. Video games did increase their collections for the third straight year, but at a much slower rate than previously. The European market for American video games was actually stronger than the domestic one. In RePlay's fall poll, 47% of operators said they planned on purchasing fewer upright video games versus just 28% who planned to buy more. For cocktail video games, which had been stung by the appearance of the "blue sky" operators, things were even worse with just 3% saying they planned to buy more versus 90% who planned to buy fewer. The variety of new video games continued to increase in 1978. After wowing at the 1977 AMOA show, Cinematronics'Space Wars went on to become the biggest hit of the year, topping both the Replay and Play Meter charts. This marked the first time a game not made by Atari or Midway was ranked #1. Indeed no non-Midway, non-Atari game managed to rank in the 6 in any of the four previous polls conducted by the two magazines. Space Wars also introduced the vector display to the industry.

First Cockpit Game: Star Fire (Exidy)

First Game To Record High Scores and Initials of Top Players: Star Fire (Exidy)

Play Meter: Pinball $62, Pool Tables $53, Jukeboxes $52, Video Games $50

Vending Times (no figures for jukeboxes): Pinball $48, Pool Tables $41, Video Games $36

Total coin-op collections

Vending Times: $2.2 billion (does not include jukeboxes)

# of machines on location (in thousands):

Vending Times (no figures for jukeboxes): Pinball (573), Pool Tables (184.9), Video Games (164.6)

Play Meter: Pinball (737.6), Arcade Games [includes video games] (469.4), Jukeboxes (447), Pool Tables (268.2)

% of total equipment, by type (Play Meter)

Pinball: 33%, Arcade/Video: 21%Phonographs: 20%

Preferred Video Game Manufacturer (Play Meter)

Atari 69%, Bally/Midway 27%, Exidy 1%, Others 3%

Restaurants: 1. Pinball Machines, 2. Upright Video Games 3. Wall Games and Cocktail Video Games (tie)

By the start of 1979, it was clear that video games had brought about major changes in the coin-op industry. When Pong made its debut in 1972, the industry was in many ways not far removed from its penny arcade roots. It was an old-fashioned industry that was often difficult for new firms to enter and sometimes closed to new ideas. It was also an industry that was struggling. Sales were flat. Jukeboxes were in decline. Top pins were selling in the neighborhood of 5-6,000 units. In 1969, Chicago Coin's Speedway sold the "amazing" total of 10,000 units. The rise of video game technology and the phenomenal success of the games themselves would transform the industry and force it to modernize. In 1978, Play Meter editor Ralph Lally wrote "The introduction of video games will probably rank as the decade's number one innovation. No one can doubt the vast number of new locations and players they brought to this industry" (though he noted that the introduction of solid state pinball ran a close second).

Circa 2000, Industry veteran Paul Jacobs, who worked for over a dozen company during his 35-year (and counting) career echoed the sentiment.

In 1978, for example, while arcade video games generated almost $400 million, pinball generated $1.4 billion – over three times as much[1]. Pinball controlled 53% of the coin-op market and it wouldn't be until 1980 that video games overtook them. According to Play Meter there were 738,000 pinball tables on location in 1978, compared to 514,000 video games and electromechancial arcade games (Vending Times gives very different numbers: 573,000 pinball games, 165,000 video games, and 9,500 arcade games). All three major trade magazines (RePlay, Play Meter, and Vending Times) agree that in terms of average weekly earnings, pinball games outranked video games in 1978. While video games may not have spelled the death of pinball – at least not in the 1970s, a better case can be made that they displaced electro-mechanical arcade games, ball bowlers, and wall games, which went into sharp decline around 1976 and had largely disappeared by 1978 (though they would later make a comeback). While video games had drawn new manufacturers into the industry, many of them left almost as fast as they entered. By 1979, the list of video game manufacturers that had disappeared or been absorbed by other companies included Digital Games, Electromotion, Meadows Games, Amutech, PMC, Mirco Games, Innovative Coin Corp., Fun Games, Electra Games, Computer Games, Amutronics, Brunswick, Ramtek, PSE, and Chicago Coin. The influx of new operators was even more chaotic and would eventually prove more of a curse than a blessing.

By 1978, few still considered the games a mere fad, but neither was it clear that they were the wave of the future and many operators remained leery of video games or saw them as just one of many options in the coin op world. It was still possible (though barely) for an operator in 1978 to ignore the games entirely. Pong had been all the rage in the early ‘70s but its reign was relatively brief and the game quickly faded from memory. By 1978, few adults could name a single arcade video game other than Pong. In 1979 that would change. On the other side of the globe, a different kind of video game was taking Japan by storm and video games would once again become a national craze – one that would make the glory years of Pong seem tame by comparison. The golden age of video games was about to begin.

Pictures

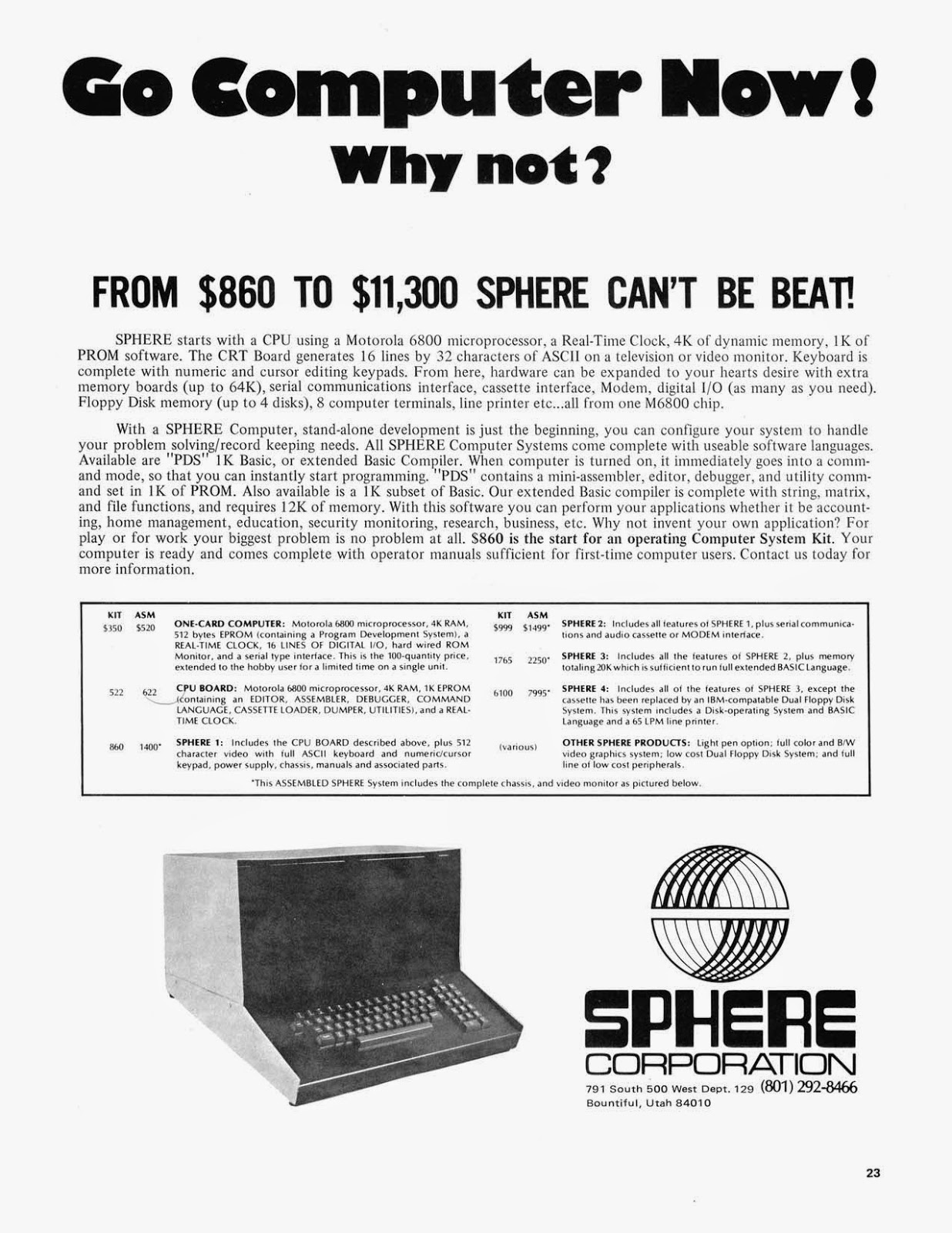

From Electronic Games, August, 1982

From January, 1984:

Some Kiddie Ride/Video Game Combos from the early 1980s:

Intermark's Poker Machine (Play Meter, March, 1979)

1978

RePlay’s annual review said of 1978 "Video games…disappointed this past year. Unfortunately, they were off in both sales and route collections in all parts of the country. It was probably the most disappointing year in the history of this college-bred phenomenon of the coin industry." They also noted that the year was "less than a banner year" for the coin-op industry in general (outside of pinball and foosball). The main issues were over saturation and poor quality control. Video games did increase their collections for the third straight year, but at a much slower rate than previously. The European market for American video games was actually stronger than the domestic one. In RePlay's fall poll, 47% of operators said they planned on purchasing fewer upright video games versus just 28% who planned to buy more. For cocktail video games, which had been stung by the appearance of the "blue sky" operators, things were even worse with just 3% saying they planned to buy more versus 90% who planned to buy fewer. The variety of new video games continued to increase in 1978. After wowing at the 1977 AMOA show, Cinematronics'Space Wars went on to become the biggest hit of the year, topping both the Replay and Play Meter charts. This marked the first time a game not made by Atari or Midway was ranked #1. Indeed no non-Midway, non-Atari game managed to rank in the 6 in any of the four previous polls conducted by the two magazines. Space Wars also introduced the vector display to the industry.

Pinball and Other Coin-Op Games

The big news in the industry continued to be the rise of pinball and especially solid state games. Replay noted that "Pinball is 'all the rage' in virtually every type of location. It's even beating out 'King pool table' in bars as the top coin-grabber in this year's poll ... a hard thing to believe…" Another issue declared that "Flipper games are the darling of the business right now." According to Play Meter average weekly collections from pinball games rose from $44 in 1977 to $62 in 1978. Replay reported in 1985 that 53% of income in street locations in 1978 and 42% of arcade income came from pinball. Bally introduced seven different pinball machines during the year that sold more than 10,000 copies, led by Playboy with 18,250 (though it wasn't released until December) and Mata Hari with 16,260. Outside of pinball and video games, Williams released its first solid state shuffle alley Topaz. Arachnid debuted English Mark Darts (which would eventually spark the electronic darts revolution). The AMOA allowed gambling games on the convention floor for the first time and distributors started to handle more than one brand of jukeboxes, breaking a long tradition.

Statistics:

# of Different Video Games Released: ca 110

Top Games

Replay: 1. Space Wars (Cinematronics), 2. Sprint 2 (Atari), 3. Sprint (Atari), 4. Sea Wolf (Midway), 5. Breakout (Atari), 6. Super Bug (Atari), 7. Starship 1 (Atari), 8. Sea Wolf II (Midway), 9. Smokey Joe (Atari), 10. LeMans (Atari)Play Meter: 1. Space Wars, 2. Sprint 2,3. Sea Wolf, 4. Sea Wolf II, 5. Super Bug6. Starship 1 (Atari), 7. Circus (Exidy), 8. Breakout, 9. Night Driver (Atari), 10. Sprint 1 (Atari)

Significant Firsts:First Cockpit Game: Star Fire (Exidy)

First Game To Record High Scores and Initials of Top Players: Star Fire (Exidy)

Top machine types, average weekly earnings:

Replay: Pins $51.50, Pool Tables $44.25, Upright Video Games $43.75Play Meter: Pinball $62, Pool Tables $53, Jukeboxes $52, Video Games $50

Vending Times (no figures for jukeboxes): Pinball $48, Pool Tables $41, Video Games $36

Total coin-op collections

Vending Times: $2.2 billion (does not include jukeboxes)

% of collections by game type (RePlay)

Street locations: flippers 53%, pool tables 18%, TV games 17%

Arcades: flippers 42%, TV games 31%, group games 12%# of machines on location (in thousands):

Vending Times (no figures for jukeboxes): Pinball (573), Pool Tables (184.9), Video Games (164.6)

Play Meter: Pinball (737.6), Arcade Games [includes video games] (469.4), Jukeboxes (447), Pool Tables (268.2)

Total dollar volume of collections, by machine type (in millions):

Vending Times: Pinball $1,430, Pool Tables $394, Video Games $308% of total equipment, by type (Play Meter)

Pinball: 33%, Arcade/Video: 21%Phonographs: 20%

# of new machines bought per operator, by type (Play Meter)

Pinball: 21, Video Games: 12, Phonographs: 5, Foosball: 5Preferred Video Game Manufacturer (Play Meter)

Atari 69%, Bally/Midway 27%, Exidy 1%, Others 3%

Most popular game types (Replay)

Taverns: 1. Pinball Machines, 2.Pool Tables, 3. Shuffle Alleys, 4. Video GamesRestaurants: 1. Pinball Machines, 2. Upright Video Games 3. Wall Games and Cocktail Video Games (tie)

Summing it All Up - The Bronze Age

The opening of new locations to coin-op games may have been video games’ greatest impact, not only because of the new revenue it generated, but because of the positive impact it had on the industry’s image. In an article in the October, 1976 issue of RePlay titled "TV Games and Respectability", industry veteran and video game skeptic Louis Boasberg explained.

[Louis Boasberg] …I will shout it to high heaven that all of us in this great industry owe a debt of gratitude to video games and the developers of same, for they have given us respectability and aboveall entree. I emphasize entree because video games have allowed operators to operate in thousands of locations where any kind of coin operated amusement game was taboo, unacceptable, and not permitted to operate in the past. To name a few of these locations: Such places as swank cocktail lounges, restaurants, hotel lobbies, hotel game rooms, airports, supermarkets, shopping malls, department stores and many others, and I might add the list is growing all the time

[Paul Jacobs] The video game was the greatest change that ever occurred in the coin-op business. It opened up a whole array of new locations for operators. Our industry is now mentioned in the same breath as the motion picture industry and the recording industry. It is the video game that did this. The industry is not viewed in the context of a smoke-filled pinball parlor anymore. We are looked upon as a very legitimate form of entertainment. The video game has had such an impact on our industry that those who view our industry today refer to it as the video game business, not the coin-op business.

For those familiar with the video game banning controversies of the 1980s or the seemingly endless campaign against video game violence, these comments may seem paradoxical, if not outright false. Prior to Pong, however, the coin-op industry had a reputation that was, I anything, even worse than it was at the height of the anti-arcade crusades of the ‘80s or anti-violence crusades of the ‘90s. Prior to the rise of video games, many considered the coin-op industry to be one step above organized crime and prostitution.

In addition to the new locations, video games also bought a host of new manufacturers and operators into the industry. While many older operators complained that they didn't know how to service the newfangled video games and solid state pins, many new operators found them much easier to maintain. Servicing gun games and pinball required work and more than a little experience. Balls had to be cleared from playfields (which required removing the top glass), stuck relays had to be unstuck, and moving parts broke frequently. With video games, however, all an operator often needed to do was wipe down the glass and collect the coins. While servicing broken video games often required the assistance of technicians, the games didn't break down nearly as frequently as their electro-mechanical predecessors.

Of course, we don’t want to overstate the impact of video games on the coin-op industry either. Looking back from the 21stcentury when video games are as ubiquitous as toothpaste, it’s all too easy to read our modern opinions back into 1978. Video games, for instance, did not render pinball obsolete overnight as some have written. Far from it. In fact, in the years 1976-78, it was the pinball game, not the video game, that ruled the roost in the coin-op henhouse. And the biggest reason was the introduction of the solid-state pin.

[Ed Adlum] During that time, the biggest event was the birth of the electronic pinball machine. It caused a two year pingame boom during which both the industry and the playing public fell absolutely in love with this updated version of the classic game. Bally dominated the market while all the remaining pin makers like Williams and finally Gottlieb got into the act.

[Ed Adlum] I remember an upstate operator named Millie McCarthy who wouldn't put a sit-down cocktail video game into any of her places for fear of someone dropping a beer mug onto the TV monitor...what we call the picture tube. In the beginning, video looked like just one more way to play a game. Even Nolan Bushnell himself once asked...and I was there when he did. . ."What else do you think we can do with this other than play tennis or soccer or hockey?"

By 1978, few still considered the games a mere fad, but neither was it clear that they were the wave of the future and many operators remained leery of video games or saw them as just one of many options in the coin op world. It was still possible (though barely) for an operator in 1978 to ignore the games entirely. Pong had been all the rage in the early ‘70s but its reign was relatively brief and the game quickly faded from memory. By 1978, few adults could name a single arcade video game other than Pong. In 1979 that would change. On the other side of the globe, a different kind of video game was taking Japan by storm and video games would once again become a national craze – one that would make the glory years of Pong seem tame by comparison. The golden age of video games was about to begin.

[1] Figures are from the Vending Times Industry Survey. Other sources give figures of $200 million spent on video games and over $1 billion spent on coin-op games as a whole.

Pictures

From Electronic Games, August, 1982

From January, 1984:

Some Kiddie Ride/Video Game Combos from the early 1980s:

Intermark's Poker Machine (Play Meter, March, 1979)

.png)