written down the titles of the papers of the people.

Q. I gather you have ordered a copy of the transcript from the University of Utah?A. Yes.

Q. And have you corresponded with Dr. Atwood to try and get a description of the course?A. I have been attempting to get ahold of Dr. Atwood, but he is not full-time at the University any more. It's been a little tough getting ahold of him.

Q. Do you have any idea when you expect the transcript to arrive?A. I think any day now.

Q. As best you can recall at the present when did you take the Senior Thesis course?[Note – This section concerns a senior thesis Bushnell claims to have written in which he describes an arcade game consisting of a central computer connected to six terminals

Nolan may well have written such a paper, but no copy of it has ever turned up and likely never will so it’s probably impossible to verify the claim.I see nothing suspicious in the fact that Nolan didn’t keep a copy of the paper (how many of you kept copies of your college papers? I know I didn’t). I’m not sure if anyone ever asked his professor about it either, but I wouldn’t have expected him or her to remember it either. Still, without the paper, or someone to corroborate its existence, the story remains unconfirmed and given the disputes over some of the other facts in question, some are going to be suspicious of the paper’s existence.]

A. I think it was the spring of '67.

Q. Can you describe in a little bit more detail what was included in that paper? You said it as a block diagram. Can you reproduce the block diagram?A. Sure. These are monitors and then I had controls feeding back to the computer. I mean, it was not a technical exercise. It was more of a written exercise.

Q. Was that the only diagram that was included in the paper?

A. I think so. It wasn't a very long diagram. Or, I mean, it wasn't a very long paper. I think that's the only picture that was there.Q. Did the paper say anything about what would be contained in the box which you have labeled on the diagram you just drew as "computer"?

A. Computer? It was a general-purpose time-sharing type computer. I will have to admit this is very foggy recollections on some of this.Q. You have drawn six small boxes connected by lines to two parallel lines and I gather you have meant to indicate that each one of those six small boxes--

A. Was a monitor.

Q. What do you mean by the word monitor?A. What do I mean now or what did I mean then

Q. What did you mean then?

A. I think I just meant the type of display that I was familiar with at the school.Q. You mean an XY type display?

A. I don't know what that was.Q. You mean the type of display used in conjunction with the Univac or the IBM 7094 that you were working with?

A. Yes. Let me take that back. I don't really know what kind--you know, it was just a monitor that you could play games on for an amusement park.Q. Did the paper include any description of the types of games that might be played don it?

A. Yes, it did.Q. What kind of games were described?

A. Space War.Q. The Space War similar to the Space War which you played on the computer--

[NOTE – Obviously if it could be proven that Nolan could not have seen or played Spacewar at the University of Utah, it would throw doubt on his account here. Conversely, if a copy of the paper ever turned up and it did in fact include a description of Spacewar it would confirm that Nolan had encountered the game by this time (though not necessarily at University of Utah)] A. Yes. Hangman, which is a word game. The question and answer game, you know, which question will flash up and you had a multiple choice answer. A baseball game.

Q. Any other games?A. I think those were the only three that I described.

Q. Would you describe what the baseball game was, how you intended it to be played?A. I intended it to be played similar to the machines that I was operating at the time in which there was a ball and a bat and you were to attempt to hit targets.

[Note – Again, Nolan is describing a “pitch-and-bat” game here, as discussed in the first post in this series.]Q. How would the ball appear at the plate?

A. I didn’t go into that.Q. Did you describe in the paper the game baseball in greater detail?

A. I just said a game that simulates the game of baseball in which a ball is pitched to a batter and the batter is controlled by the player. The attempt is to hit the ball straight back to get a home run. If you deviate from the center, then you can get anywhere from a single run to an out. Three outs—and it was a dime in those days. Three outs and you had to put in another dime to play.Q. Did you state in the paper whether you expected that there be a symbol on the screen which a player could maneuver somehow?

A. Well, I mean, if you’re going to have a ball on the screen I suppose that would be symbol. I don’t think I used that verbiage.Q. Was the bat to be moved on the screen?

A. Obviously.Q How was that to be done

A. By pushing a button.Q. What would occur when one pushed the button?

A. The bat would swing.Q. Was this described in the paper?

A. I really don’t remember. I just remember that I described a video version of the games that were around at that time.Q. Did anyone other than you and Dr. Atwood and your wife see the paper?

A. I really don’t know.Q. Do you think other persons might have seen the paper?

A. I think it is possible. If I knew who they were I would know by now. I mean, I would have talked to them by now. Q. So you have searched for other people or attempted to recollect who they might be?

A. I have tried to get some confirmation on that, yes.Q. Have you talked to your wife concerning whether she remembers the contents of that paper?

A. Oh, yes, obviously.Q. Obviously yes?

A. Yes.Q. Does she remember what was in that paper?

A. Not in great detail.Q. Does she remember the description of the game baseball?

A. No.Q. Did you ask her if she read the description of the game baseball?

A. No, I didn’t.Q. What is your wife’s present residence?

A. 3872 Gibson. Santa Clara.Q. What is her name?

A. Paula Bushnell.Q. I assume that you and your wife are divorced?

A. Yes, we are. I’m not sure if that means you’ve got a friendly witness or not.Q. How many monitors did you contemplate could be attached to a single computer for the playing of the game?

A. I thought six was—the speeds and the kinds of information at that time.Q. Did you have any thoughts as to what was the capacity of the computer would have to be to play six games?

A. It had to do an awful lot with how much refresh you had to do, so it meant how smart the computer was. Or the terminal I should say.Q. Did you do any calculation to figure out what the correlation might be between the capacity of the computer and, as you put it, how smart the monitor was in order to get an acceptable apparatus?

A. No. I think I just wet my finger—you know, I was trying to get the paper out and I didn’t care about technical excellence because I knew I was going to get graded on punctuation. The nice thing about schools is that you don’t have to build anything that you design.[NOTE – This raises a semi-important point. From a legal standpoint, even if Nolan did write such a paper, I do not find it likely that it would have constituted an instance of “prior art” that would invalidate Baer’s patents. A mere description of a system in which a central computer controlled remote terminals, even one that included descriptions of games that involved imparting motion or detecting coincidence, probably would not have sufficed. He (IMO) would have had to have described the system in sufficient detail that it could have been built – including a description of exactly how he was going to detect coincidence and impart motion And (again, IMO) he would have had to have described how to do so with a raster display. I’d also imagine he’d have to have done so in a manner similar to that used by Baer.

From a historical standpoint, in regards to establishing who was the “father of the video game industry”, I’m not sure this paper would be of much use either. By his own admission, Nolan’s idea (if it existed) did not have the makings of a viable commercial product at this time. Its main value, I think, would be in establishing when Nolan first got the idea that eventually led to Computer Space.] Q. Did you ever build an apparatus as it was shown in the paper?

A. I attempted to later on. I mean, a time-sharing system.Q. When did you attempt it or when did you first start to attempt it?

A. I would say the middle of 1970 or early 1970.Q. Did you complete building the apparatus as described in the paper?

A. No, I didn’t. I just got to a paper design.Q. Is there any particular reason why you stopped working?

A. Yes, I found a better way.Q. What way was that?

A. Well, in the using of a computer and a monitor, the calculations you were talking about, I kept going through them finding that I was running out of time doing the kinds of things on the six monitors that I wanted to. So then I cut it back to four monitors and in doing more interface and more software I found that I was again running out of time. Since I decided that we had to design the monitor because the terminals at that time were very expensive, I was building my own monitor, a special-purpose terminal for this thing. Each time I would find in the computer that I was running out of time I’d take some of the functions out of the computer and put it into a slightly more intelligent terminal. After I went through the loop two or three times and each time finding conditions in which the computer would run out of time, I took a look at the terminals and I said, “Gee, they’re getting so smart, why do I really need that? Let’s throw away the mini-computer and put it all in the terminal.” That’s really now the stand-alone games evolved. I was really happy because it made a lot more economic sense, you know, once you can split them apart so that your stand-alone units, limiting you market to the large amusement parks, you know, that would have to take the six or seven terminals to make it justifiable economically. [NOTE here that Nolan doesn’t claim to have actually built a system with multiple terminals (as some seem to have erroneously concluded). This was all done on paper.]

Q. As far as you know was it ever actually done in 1969 that the games were played on a raster scan display setup?A. To the best of my knowledge, no, they weren’t

Q. I believe you stated that in early 1970 you attempted to build an apparatus for playing games similar to the one described in the paper which you wrote at the University of Utah?A. Right.

Q. Prior to that did you do anything or attempt to construct or interest anybody else in constructing the apparatus as described in that paper?A. No, I didn’t.

Q. did you ever show the paper to anybody at Lagoon Corporation or Amusement Services Corporation?A. No. I think I talked to some of the people at Lagoon saying you know, “Gentlemen, it would be neat if we could have a computer out here and hook it up.” But, you know, it was one of those things where when you’re talking about six games that would cost as much as a roller coaster, it was kind of an academic kind of discussion.

Q. How much did you think six games would have cost at that time?A. Using that system probably a quarter of a million dollars.

[NOTE - I may be missing something obvious here but it seems that Bushnell could have built a cheaper system using the DEC PDP-8 (generally considered the first successful, mass-produced minicomputer), which had been released in 1965 and cost around $18,000. Perhaps it initially cost more than that or perhaps it was impractical or incapable of driving multiple displays, or maybe he just wasn't aware of it.]

Q. At that time would that have been an economic investment as far as you know to get six games?A. I don’t know. The question then becomes if you had six of them—well, let’s put a pencil to it. If you could get fifty cents a game and it plays in two minutes, that would be $15 an hour times six, that would be $90 an hour. If you amortized the thing over three years, what does it come out to? Say that you want a ten-percent return on your capital. A quarter of a million dollars and a ten-percent return. If you have two years which is 24 months--this says that you would have to make $11,000 a month. $11,000 a month at $90 an hour, let's divide 24 into that. That is $490 a day. So that says that you could just barely make it if you could keep the machine going full tilt for five hours a day or six hours a day, rather. So it was marginally doable based on some good assumptions.

Q. At that time was fifty cents a game a realistic price?A. Well, I'm saying that games were really great. The market at that time was 25 cents. So it says that you would have to keep the game going for 10 or 12 hours. I don't think I would invest my money in it.

Q. Do you have any documents relating to your attempts to build the system of your paper in early 1970?

A. Yes, we do. They are right here (indicating).

Q. You have pointed out two files, one labeled "Data General" and the other one labeled "System Planning, Nova Interface.”

A. Right.

Q. And those are the only two files?

A. That's all that I could find. They were down in the bottom of a box of all kinds of junk.

MR. WILLIAMS: I would like to have the Reporter mark as Atari Exhibit 39 a manila file bearing the label "Data General,' and as Atari Exhibit 40 a manila file bearing the legend "System Planning, Nova Interface."

I think maybe, Mr. Reporter, if you could mark each paper in each one of these files as in the case of Exhibit 39, 39-1 through 39 whatever it takes, and likewise with Exhibit 40. (File folder labeled "Data General 'I"was marked Atari Exhibit 39-1through 39-7 for Identification.)

(File folder labeled "Legend System Planning, Nova Interface" I was marked Atari Exhibit 40-1 through 40-18 for Identification.)

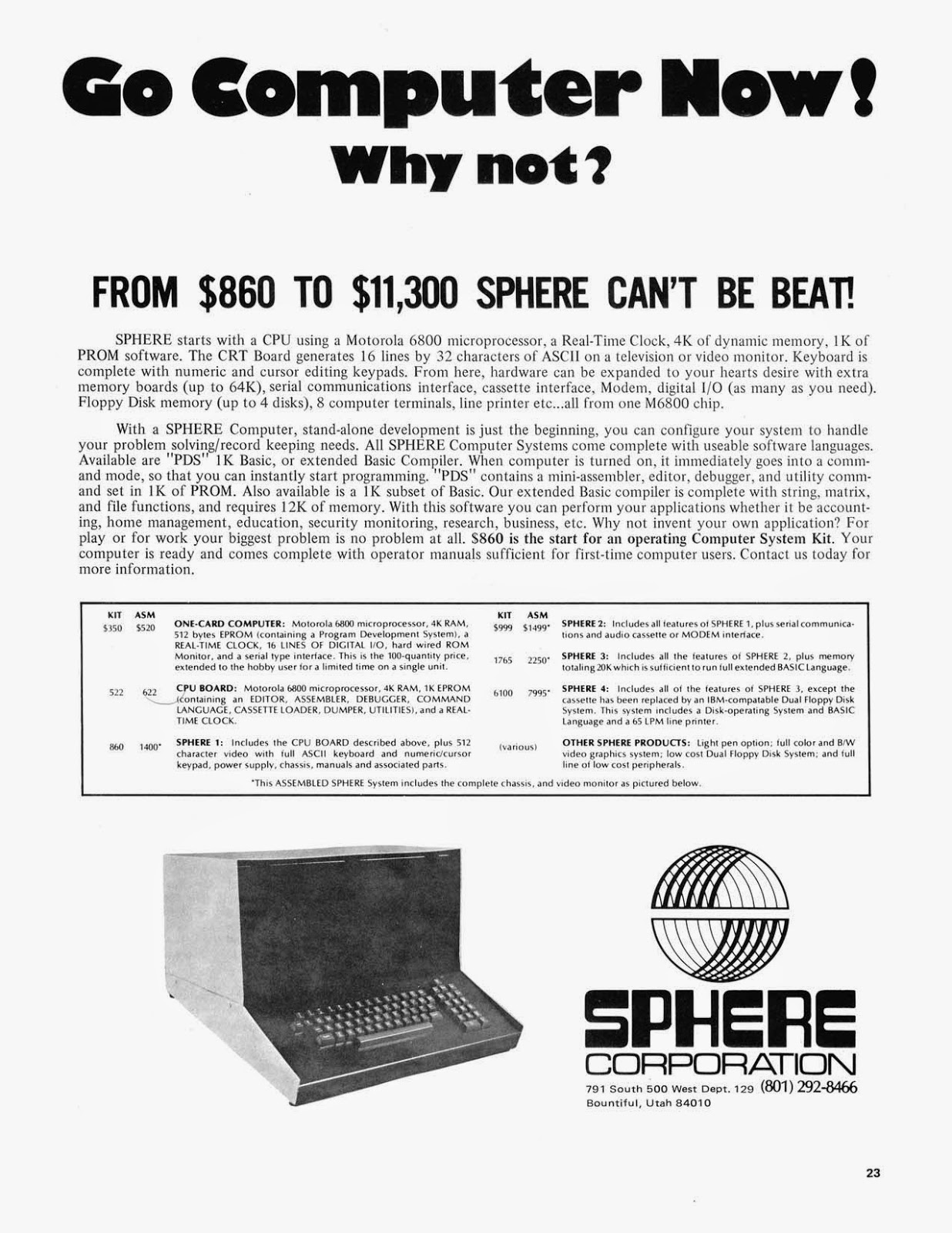

[NOTE – This section deals with the Data General Nova. I’m sure most of you already know this, but the seeing an ad for the Nova was what convinced Nolan that his idea might be practical. Data General was founded by several former DEC employees in 1968 to produce low-cost minicomputers. The Nova was a minicomputer that was introduced at a base price of $3,995 (far cheaper than DEC’s PDP-8, considered by many the first successful minicomputer).] MR. WILLIAMS: Q. Mr. Bushnell, I hand you Atari Exhibit 39 and the document which has been marked 39-1 and ask if you can identify that document for me.

A. Yes.

Q. What is it?

A. It's a letter that I was going to-- No. It's an envelope. It's a letter in which-

Q. You are referring to 39-2 as the letter?

A. Yes. 39-1 is an envelope. --in which we were going to order a Data General computer.

Q. You say, "We were going to order a Data General computer"?

A. The company. The Syzygy Company at that time.

Q. And Syzygy at that time was a partnership; is that correct?

A. Yes.

Q. Consisting of you and Mr. Dabney?

A. Right.Q. How did this relate to your infiltration of the system of your prior paper? A. Well, we had gotten to a point where we felt that we had feasibility on the system and so we needed a machine to actually build one.

Q. The letter-- A. Well, what it was, we wanted to get the best price we could so we ordered six of everything except for one item which I guess we needed more than that. Because we didn't have any money. So we wanted to, you know, give the impression at least that we were high rollers.

Q. Was that letter ever sent?

A. No, it wasn't.

Q. It appears to bear the date January 26, 1971.

[NOTE – this letter seems to indicate that Nolan still hadn’t entirely dropped the idea of using a Nova as of late January, 1971.]

A. Correct.

Q. Was it written on or about that date?

A. Yes, it was.

Q. Prior to the time of writing that letter had you built any devices for the playing of games using a cathode-ray tube according to your system of your prior paper?

A. Yes. We had put some stuff together as far as a monitor goes. See ,wi1h this system we were building terminals to hook on which this would drive and we had established at that point that we could get a tube hooked up to a raster scan responding to that and I think we moved some objects around.

Q. Well, on January 26th of 1971, you were considering using a raster scan display on your system?

A. Yes.

Q. You say you put a monitor together prior to that January 26th, 1971 date. Was the monitor as you had built it useful for playing games?

A. Well, the way we had done it, it possibly could have been. We were trying to build--Spacewar was the game that we were trying, and Spacewar needed some very complex calculations and the device that we lashed up didn't have the ability to do complex calculations. It was more of a display device.

Q. You say it could have been used for playing games, but was it used for playing games prior to that January 26, 1971 date?

A. Well, if you mean we moved objects around on it and had a little bit of fun, yes, we did. It goes into our definition of what is a game. It wasn't anything that kept score or that I said, "Whoopee, I beat you.'' But we did move objects on it.

Q. How did the objects that were moved appear to the participants?

A. Well, one was we had a rocket ship that would move up, down, right or left. I guess before that we had ~ a square that would move up, down, right or left. Then we hooked in a diode matrix and turned the square into a rocket ship.

Q. How did the participant effect this motion up, down, right or left?

A. Flipped switches.

Q. Was there only one rocket ship or square as the case might be on the screen at a time?

A. Well, at what point in tine are you talking about?

Q. Prior to the January 26th, 1971 date.

A. Yes. It was just one object. Just a second, I'm going to ~ take that back. There was only one independently moving object. In developing the objects youcan gate them in and out and there were, you know--during the first gating, you know, there could have been 48 objects and then you gate it out again and it turns--or I guess it would be 64 and then it goes down to 32 and the more gating that you do the fewer things until you finally get down to just one object. But we had beaucoup objects on the screen many times.

Q. As I understand it, even though you may have had many objects on the screen at the same time, if one moved they all moved with--

A. Correct.

Q. I show you a document which has been marked 39-3 and 39-4 and ask if you can identify that?

A. That's a listing that came from one of the trade journals, and I don't remember which one it was, which listed all the mini computers that were on the market at that time, their approximate costs and how fast the cycle time was and what the architecture of the machine was. It was sort of a thing that we went through to see if there wasn't a cheaper system that we could buy that would do essentially the same thing.

Q. Essentially the same thing as what?

A. The same thing as the Data General unit that we felt probably was as good a buy on the market at the time for what we wanted.

Q. I notice that those two documents bear the dates August 1970. Were these documents that you were considering after the date of January 26, 1971 or prior to that time?

A. Well, it was prior because, you know, obviously we had made a decision at the time this letter was written as to which computer we wanted and we had been looking at this quite a bit before August 1970 and was very happy when they published this because it made us evaluate a lot more units.

Q. You said you were looking into it quite a bit before August of 1970. I gather from your prior testimony that all of your activities were during the year of 1970 with respect to the building of this?

A. That is true, in terms of actually putting any hardware together or, you know, drawings.

Q. ·I will hand you Exhibit 39-5 and ask if you can identify that?

A. It's just basically a little further detail on the Nova computer series.

Q. This was the computer series that you were considering using in your system?

A. That's correct.

Q. Was that the Nova 1200 as described in this exhibit?

A. Correct.

Q. I show you Exhibit 39-6 and ask you if you can identify that?

A, It's an OEM blanket quantity and cumulative discount agreement. That was the thing that we were planning to I really buy a bunch of these things so we wanted to get the price out of the chute that we could.

Q. Can you identify Exhibit 39-7?

A. It's a Super Nova pricelist and it goes through the options and the things that you want. It's essentially the source document that allowed us to write this other letter.

Q. That is Document 39-2?A. Right.

Q. 39-2 appears to include a list of various components and associated prices. I ~ender if you might go through this list and tell us which each one of the items identified by a number is, such as 3101, 8102, et cetera.

A. It's been a long time. I would just have to go through these things. They are essentially parts to a mini computer.Q. So far as you know the identifications given in 39-7 of the various type numbers I believe are the same type numbers referred to in 39-2?

A. Right, yes.

Q. Is the description given in Document 39-7 of each of those type numbers accurately reflective of the description of the items listed in the letter of 39-2?

A. I think so, unless we made a mistake.

MR. HERBERT: I object. I don't think there is any description of an item on 39-2, nothing more than a type number.

THE WITNESS: But the description is in here.

MR. WILLIAMS: Q. Do the descriptions of the type numbers shown in document 39- 7 accurately describe the units listed in 39-2?

A. Yes.

Q. Are the prices shown in 39-2 opposite the corresponding units a unit price?

A. I think that was an OEM discount based on the quantity, discount price.

Q. That was the price you expected to pay for the units if you had actually purchased them from Data General at the time?

A. Right.

Q. So that, for example, one 8101 would have been $1,617?

A. Right.

Q. At the time of the preparation of the letter 39-2 did you have an estimate of what the cost per game would be in the system you were constructing?

A. Yes.

Q. Do you know wb.at that estimate was?

A. I think it was around $1,000.

[NOTE – This price, if accurate, makes more sense to me. At the prices that are quoted for the Nova in most sources, I don’t think Nolan’s idea would have been practical. Wikipedia claims that the base price was 3995 price (ca $27,000 in 1913 dollars, depending on which method you use), which I think is still far too expensive for a practical arcade game (not to mention Wikipedia’s claim that the base unit was all but useless without adding core memory, which added another $4,000 to the price).

I am not sure what model the $3,995 price referred to. From the pricelist above, it might have been for the 4001, which was more expensive than the 8101 that Nolan was apparently considering.]

If Nolan could have got a volume discount that lowered the price to $1,000 per game, it would make for a much more practical product. Whether or not he could really have gotten that price I can’t say.]

Q. At that time were you considering using six games on each system?

A. It was either six or eight. I think I started out with eight and then backed into six as I started running out of tir.ie on the computer.

Q. Did you ever order any computers from Data General for this system?A. No, I didn't.

Q. Did you order computers from anybody else for this system?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Did you ever complete building this system?

A. No, I didn't.

Q. I hand you Atari Exhibit 40 and ask you if you can identify Document 40-1?

A. This is a letter from Bob Washburn who was the sales engineer in the area for Data General. We had kind of been stringing him along because we weren't ready to commit the dollars and we had sort of told him, "Yes, the order is coming. The order is coming." I think this letter is to just sort of jack us up and trying to push us into a close. It was during this period that I had pretty much decided that I was not going to go the direct computer route but was going to go to a single stand-alone unit.

[NOTE – so it seems that sometime between these two letters [i.e. between January 26 and February 16], Nolan and Ted had decided to go with a single computer.]

Q. During what period was this that you just referred to?

A. Between I got that. the time of composing that letter to the time that Because it was--I was almost ready to go but I just wanted to go back and check to make sure that the system as I had configured it made sense. I wanted to make sure the thing was doable, and so I wanted to get closer-- I had found a place where I could rent a Data General computer and I had gotten a little bit closer to a guy that was there who wastrying to sell me some time on the machine. He pointed out something that I had failed to take into consideration on my initial calculations and it scared me into thinking that maybe I wasn't even going to be able to get four monitors to go. So at that point I decided that I really needed to change one of my design at that time and that pushed me into the thinking of just doing it all hardware and not doing it software with the computer.

NOTE – I am not sure what the “something” was that Nolan had failed to take into consideration. Perhaps it was the fact that the system needed extra memory to be useful. That is pure speculation, of course, and I really don’t know the actual issue was.]

Q. And the period during which this occurred that you are referring to was the period between the dates of 39-2 and 40-1?

A. Right.

Q. What was the date on 40-1?A. February 16, 1971.

Q. I show you a document 40-2 and ask if you can identify that, please.

A. This was the interface unit that took the data from the computer and displayed it on the TV screen, part of the interface unit.

Q. Was that part of the monitor which you were considering?

A. Right.

Q. Was that apparatus ever built?

A. No, it wasn't. well, parts of it were. This part was never built (indicating).

Q. Which part is that?

A. That is 40-7.

Q. What is shown on 40-7?

A. This was basically the part that made the monitor talk to the computer.

Q. Was there a name for that part?

A. I didn't put it on. I think I always called that the interface card. This other one would probably be called the address card.

Q. What document are you referring to?

A. Oh. 40-2

MR. HERBERT: It would be called what?

THE WITNESS: The address card. I'll be darned if I know what 40-3 is. I would have to think about it for a minute.

MR. WILLIAMS: Q. Is 40-3 another diagram associated with the monitor of a diagram of a portion of the monitor?A. Yes. All of these have to do with the monitor.

Q. By "all of these”, you are including--

A. 40-6, 40-8, 40-10, 40-11, 40-14, 40-15, 40-17. Portions that were built were the sync generator and the--

Q. Do you know which diagram the sync generator is?

A. I'm not sure. Frankly, I don't see the sync generator diagram here. I think the only reason that we have these documents are these are the parts that ended up not being used in the ultimate system and the other stuff got reworked and used and ultimately in the filing system and where they are heaven only knows. I was actually surprised I even found these things.

Q. By "the ultimate system" you mean the stand-alone games?

A. Right.

Q. Do you think that the drawings that were reworked into the stand-alone game still exist? A. I just have no way of speculating on that.

Q. Did you look for them?

A. Yes, I have.

MR. HERBERT:· These are among the things that I have asked Mr. Bushnell's secretary to go through and try to find and she has indicated that for all of the games there may be the files of 20 different engineers. She is going to try to get the beginning ones for those two games tomorrow and try to zero in on this particular one after that.

MR. WILLIAMS: Q. You started saying that you had built the sync generator?

A. Yes.Q. Which other portions did you build?

A. Some motion circuits and a scanning matrix, video amplifier.

Q. What was the purpose of the sync generator?

A. Well, to get the scans going. You have to have a frame of reference.

Q. This was to generate the scan for the cathode-ray tube display?

A. Right.

Q. What was the purpose of the motion circuits?

[NOTE – the issue of who designed the motion circuit for Computer Space is one of the major bones of contention between Bushnell and Dabney. Ted claims the design was entirely his while Nolan says it was his. I will not get into the merits of the claims here.]

A. To put the objects on the screen and move them around. Actually, the motion circuits that we used at that time were more exercisers to take the place of the computer because the way we had it was that the computer would put out an address word that would tell the monitor where to display the object and by putting in counters you could simulate that address word and move objects around the screen. That turned out to be the essence of the way it was instead of being an exerciser ultimately taking the place of the computer it replaced the computer. Did I make sense en that?

Q. What do you mean by the term exerciser?

A. Well, to get your hardware working a lot of times you need a very predictable signal so that you know that your hardware is working so that if you get information out of the computer you can make sure that it's not--you know, you have a problem sometimes whether it's the computer that's fouling up or whether it's your hardware. So you develop a little very simple computer, you would say, which we call an exerciser which would essentially be partitioned outside of the system, but to the system would look like a computer but without all the bells and whistles as far as the capability that the computer would have.

Q. Was an exerciser to be used with the monitor when the monitor was attached to the computer as you intended in your system?

A. Initially, no. The exerciser would be taken off and the computer would be hooked where the exerciser was.

Q. But at some later time it was to be used with the monitor as it was attached to the computer?

A. When I decided to not go with the computer system the exerciser was modified so that it did more things. What essentially happened is I made a very sophisticated exerciser which ended up playing the whole game instead of the computer doing it.

Q. What as the purpose of the scanning matrix circuit?

A. It's relatively easy to just put square blobs on the screen. The matrix was to turn the blob into a rocket ship.

Q. That the diode matrix?

A. Correct.

Q. What was the purpose of the video amplifier?

A. To make it talk to the television set at levels it could see.

Q. To make what?

A. The signal, the output of the computer.

MR. WILLIAMS: Let's take a brief recess.

(Short recess.)

To be continued.Sine I didn't have many photos for this one, here are a couple of Atari-related ones I came across recently.This one is from Atari's 1978 distributor meeting. This one had an old west theme. Unfortunately it doesn't identify who the people are. Front and center (in the loud pants) is Frank Ballouz. Behind him, I think, is Steve Bristow. I think that's Gene Lipkin in the sombrero. One of the females may be Lenore Sayers or Sue Elliot. This one appeared in the February 1974 issue of Oui.